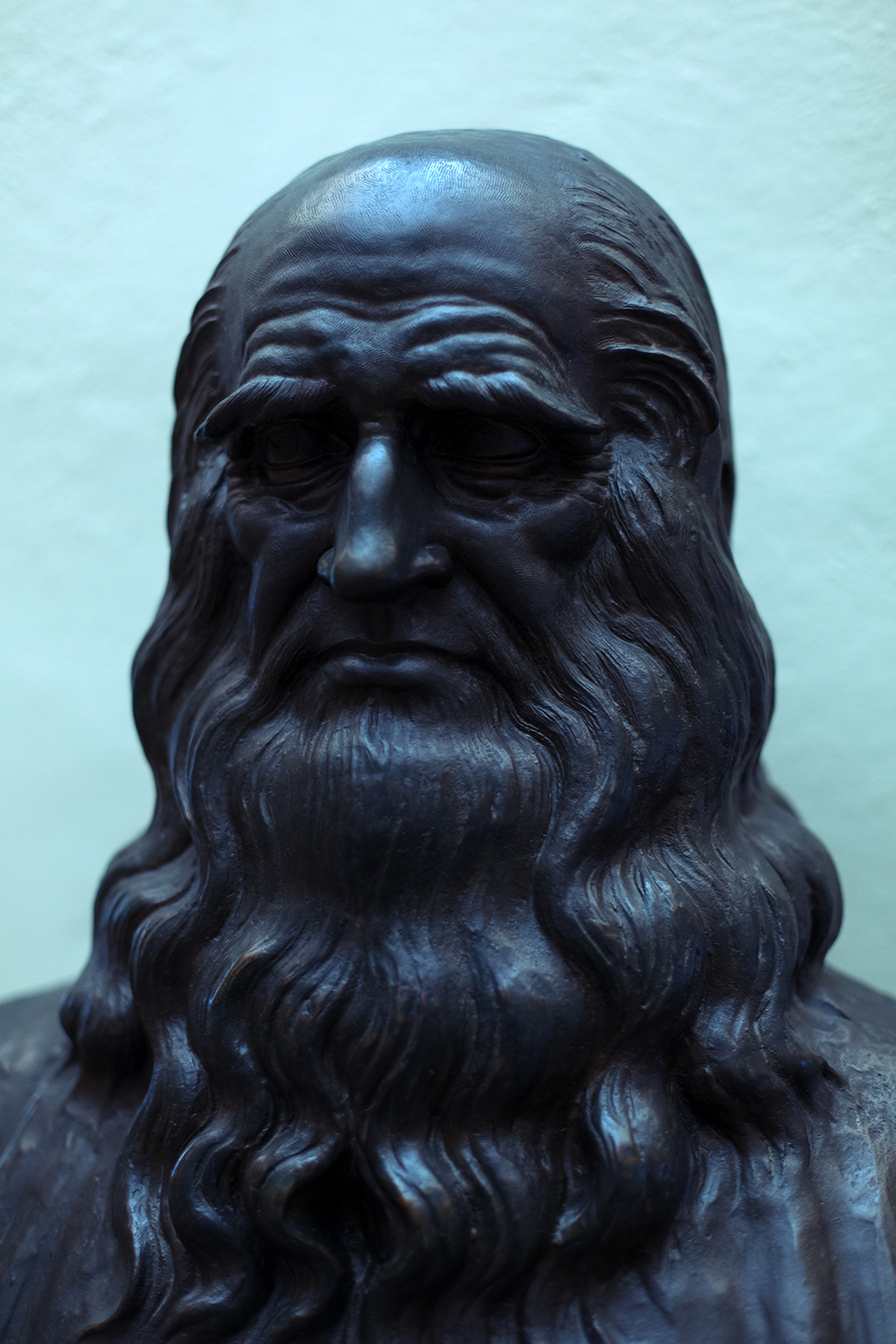

A preview of my photographic work on Leonardo da Vinci

On May 2, 2019, the fifth centenary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci occurred, a celebration of one of the most renowned archetypes of the “universal man” typical of the Renaissance time. Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was born in Anchiano (municipality of Vinci) on April the 15th 1452 and he died in Amboise (France) on May the 2nd 1519. He spawned his interest in the most different fields of art and knowledge; he dealt with architecture, sculpture, he busied himself in drawing, he wrote essays, he was a scenographer, anatomist, musician, designer and inventor. He is considered one of the greatest geniuses of all time.

During 2018 I have further deepened my studies about this artist by developing a photographic research; I have retraced his life, following the “traces” he has left, the hypotheses that concern him and the testimonies of his influence on arts, technology and today’s life. Starting from my own land, Romagna, where Leonardo lived and worked for Cesare Borgia, renovating the fortifications of the local Rocche (castles), later I visited Vinci and Florence where the artist lived and spent his childhood. In Florence I traced back some of Leonardo’s official heirs, including the Maestro Franco Zeffirelli, one of the world’s most renowned Italian directors. I explored and photographed the Valmarecchia and the Iseo Lake, identified by some recent studies as the backgrounds Leonardo painted in some of his pictures (the Mona Lisa and the Virgin of the Rocks), managing to find the exacts spots described in the studies. In Forlì I have photographed the “Da Vinci” robot, the most evolved robot system for the mini-invasive surgery, during a surgical procedure to remove a tumour. Finally, in Milan, I have documented the wing inside the Museum of Technology dedicated to Da Vinci’s genius.

INTERVIEW WITH PIPPO ZEFFIRELLI

Franco Zeffirelli, born Gian Franco Corsi Zeffirelli (Firenze, 12 febbraio 1923), is one of the world’s most famous Italian directors. Due to a serious illness he no longer appears in public and I could not interview him. In his place I had the opportunity to talk with Pippo Zeffirelli, Franco Zeffirelli’s son and vice president of the Zeffirelli Foundation which manages the Museum. An official research in 2016, conducted by Alessandro Vezzosi and Agnese Sabato, of the Ideal Leonardo da Vinci Museum, has identified 35 heirs of Leonardo da Vinci, among whom Franco Zeffirelli, who was already aware of this lineage.

A curious analogy links Leonardo Da Vinci and Franco Zeffirelli, both of them were not acknowledged by their own fathers.

Zeffirelli was born of an extramarital relationship between his father and his mother: they were both married to other people. The mother and her respective husband already had two children but, following an accident, the man could no longer father any children. This was a known fact in Florence and for this reason he could not recognize Franco. The mother was an important seamstress at the time and Franco Zeffirelli was born in a beautiful building in Piazza della Repubblica where there was an atelier, a piano (the mother loved classical music) and much more. His true father always visited him in secret and, when he became a widower, he recognized him. Zeffirelli is an invented surname: since he could not have the surname of his father nor that of his mother's husband. In the inscriptions at the Spedale degli Innocenti (Innocents’ Hospital) (the word “spedale” comes from the Florentine vernacular; the name refers to the “hospital of the abandoned children” quoting the biblical episode of the Massacre of the Innocents) they used the alphabet letters to name the orphans and, the day in which Gian Franco was brought there, they had reached the letter Z. Since his mother loved the opera, she wanted to name him Zeffiretti, from Mozart’s Idomeneo; however, they misspelled it and the name became Zeffirelli. At the age of 17 he was recognized by his father, a widower by the time, receiving his surname: Corsi. He could not recognize him before because he had a very jealous wife with whom he only had a daughter. His wife resented the fact he had had a boy with another woman. If truth be told, the father had other extra-marital children: he imported fabrics and provided many tailors in Florence and evidently had a certain charm and must have met and satisfied many women because the Maestro in the end discovered five or six half-brothers and sisters; some of them he met later in his life. For example, he found out about a brother during the Second World War; at that time the Maestro was a partisan and had taken refuge in the hills. He already spoke English fairly well and started acting as an interpreter for the English. One day he decided to go down to Florence to visit his father but, along the way, he and a dozen partisans were arrested by a group of fascists. Taken to the barracks, he met this guy behind the desk that filed the arrested boys, asking for the name and surname, and when Zeffirelli’s turn arrived, he gave the whole name: Gian Franco Zeffirelli Corsi, son of Ottorino Corsi. The officer, surprised, asked him "Are you Ottorino's son?", "Yes", at that point he called a guard and had Zeffirelli shut in a room next door. After about half an hour the father arrived in the room where the filings took place and Zeffirelli was brought back too. Surprisingly, the father began patting the officer, telling them to forgive the boy, a fool and a misfit, but in the end quiet and kind, and asked to let him go. The Maestro was released and, going away with his father, asked him who the Fascist was and his father replied "He was your brother".

The fact that his father acknowledged him only later in his life influenced the Maestro or the works he produced?

The Master had a very sad and hard childhood. In the first two years of his life he was raised by a nurse and then his mother (Alaide Garosi Cipriani), who in the meantime had lost her husband, had to move to Milan where the woman settled with a daughter. They lived there for about 4 years, until his mother died of tuberculosis, leaving the Maestro alone. The father, through his cousin Lide, fetched him. A strong bond was created with the Aunt Lide who took care of Zeffirelli, educating him and making him study, thanks to the financial support of his father who, when he was a widower, was convinced by Lide to get closer to his son to bind a relationship. When he was a child of 6-7 years old, his father’s wife was so furious about him (since he was an extramarital son) that she used to insult him out of school, calling him “little bastard” and biding him to leave Florence; the 1999 film “Tea with Mussolini” is based on these episodes. I think he suffered very much; was his career affected by these facts? It’s difficult to say. I believe he was a very smart child, willing to do things and with a strong personality. He never married and, at a certain point, he adopted Luciano and me to create his own family.

Genius is another common element between Leonardo Da Vinci and Zeffirelli.

The Maestro, although no Leonardo, was a full-fledged artist: from directing, to set design, to costume, to writing books, in short he is a genius too, hardly because of him being Leonardo’s descendant, more likely for a predisposition of the boy and perhaps also thanks to the high-level teachers he found at school. I remember that, in the year in which he graduated from the Institute of Art, he always studied with three friends and all three became great professionals: Piero Tosi, the greatest costume designer in the world, who worked with Visconti, De Sica, Fellini, Pasolini and who also received an Academy Honorary Award; Danilo Donati, who was another genius and who won two Oscars: one for the costumes of Romeo and Juliet by Zeffirelli and one for Il Casanova by Fellini, and Anna Anni, who perhaps was less renowned, but this because she loved to teach and devoted to taching a lot of time, but she too worked a lot with Zeffirelli.

How did Maestro Zeffirelli discover he was one of Leonardo’s descendants?

He always knew it although it was not an established fact, others have done it later (see the official search in 2016). The father had told him many times. For example, at the premiere of the "Romeo and Juliet" theatrical show in London, Maestro Zeffirelli was very excited at the idea that the Queen of England would be present and his father said to him "Keep your head up because she might be the Queen of England, but you are Leonardo da Vinci’s descendant!”

I trust that holding the responsibility of keeping, promoting and passing down Maestro Zeffirelli’s work is quite demanding. Did you give up something to pursue this task?

For fifty years I have worked in the field of cinema, especially with the Maestro, but I also made films with Francis Ford Coppola, ("Cotton Club"), James Ivory ("A Room with a View") and others. Later I was adopted by Zeffirelli and when he fell ill, I decided to leave the United States, where I lived, to move permanently to Italy to take care of him, help him and carry out family and professional commitments. When we created the Zeffirelli Foundation, it was my turn to deal with it and monitor its management. I do not miss anything, maybe the only thing is that I’m getting quite old, I'm 70, and this commitment will occupy me until the end of my days (he smiles). The adoption occurred when I was already a grown up person, about 25 years ago, the Maestro had already proposed it to me before but I wanted to wait for the death of my father. I could not allow it before.

Do you and your father have a favourite work among the whole Leonardo production?

How could one not love Leonardo's work? Everything he did came from a deep and profound study. My father, among other things, wanted to work on two very ambitious projects that will remain unfinished. The first was a film about Dante's Inferno, whose sketches are present here in the museum in the Sala dell'Inferno. The second was a film, entitled "The Florentines", on the Florentine Republic in which Michelangelo and Leonardo were summoned at the same time: the first to realize the David and the second to strategically divert the course of the Arno during the conflict with Pisa. The film would have deepened the relationship between these two giants who loved each other and hated each other because of mutual envy. There is a marvellous description of life in Florence at the time, of the homosexuality of Michelangelo (Leonardo’s homosexuality is less known) and much more. While we were setting up things for the film we deepened and studied the life of Leonardo and his inventions, learning their greatness. It would have been a stunning film, with a maniacal care for every detail, as only the Maestro could do.